“The air is the only place free from prejudices. I knew we had no aviators, neither men nor women, and I

knew the Race needed to be represented along this most important line, so I thought it my duty to risk my

life to learn aviation…”

– Bessie Coleman

By Kate Stow

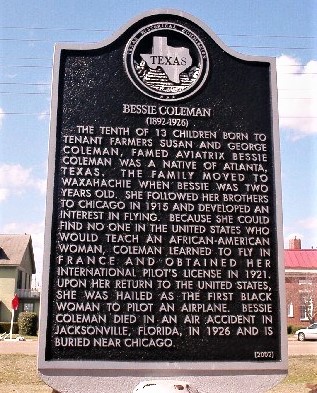

On January 26, 1892, a baby girl was born to George Coleman, whose grandparents were Cherokee Indian,

and Susan Coleman, who was African American. The girl they named Bessie was the tenth of thirteen children

born to the couple. She spent her first two years in her birthplace of Atlanta, Texas, before her family moved

to Waxahachie, Texas.

Beginning at the age of six, Coleman began walking four miles each day to her segregated, one-room school,

where she loved to read and established herself as an outstanding math student. Being sharecroppers, the

Colemans routine was interrupted each year by the cotton harvest. When George moved to Oklahoma in

1901, his family remained in Texas.

At the age of 12, Bessie was accepted into the Missionary Baptist Church School on scholarship. When she

turned eighteen, she took her savings and enrolled in the Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal

University in Langston, Oklahoma (now called Langston University). She completed one term before her

money ran out and she returned home.

She developed an early interest in flying, but African Americans, Native Americans, and women had no flight

training opportunities in the United States. At the age of 23, Coleman moved to Chicago, Illinois, where she

lived with her brothers. She saved her money from her job as a manicurist at the White Sox Barber Shop.

There she heard stories of flying during wartime from pilots returning home from World War I.

She took a second job at a chili parlor to save money in hopes of becoming a pilot. American flight schools of

the time admitted neither women nor blacks, so Robert S. Abbott, founder and publisher of the Chicago

Defender, encouraged her to study abroad. Abbot publicized Coleman’s quest in his newspaper and she

received financial sponsorships. She finally had enough to enroll in flight school – in France.

She earned her pilot license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale on June 15, 1921, and was the

first black person to earn an international pilot’s license. She was also the first woman of African-

American descent, and also the first of Native-American descent, to hold a pilot license.

With the age of commercial flight still a decade or more in the future, Coleman quickly realized that in order to

make a living as a civilian aviator she would have to become a “barnstorming” stunt flier, performing

dangerous tricks. She returned to Chicago to look for someone to train her, but had no luck.

In February 1922, she sailed again for Europe. She spent the next two months in France completing an

advanced course in aviation, then left for the Netherlands to meet with Anthony Fokker, one of the world’s

most distinguished aircraft designers. She also traveled to Germany, where she visited the Fokker Corporation

and received additional training from one of the company’s chief pilots. She then returned to the United

States to launch her career in exhibition flying.

Bessie then became a high profile pilot in notoriously dangerous air shows in the United States. She was

popularly known as Queen Bess and Brave Bessie, and she hoped to start a school for African-American fliers.

“Queen Bess,” as she was known, was a highly popular draw for the next five years. Invited to important

events and often interviewed by newspapers, she was admired by both blacks and whites. She primarily

flew Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” biplanes and other aircraft which had been army surplus aircraft left over from the

war.

Bessie made her first appearance in an American airshow on September 3, 1922, at an event honoring

veterans of the all-black 369th Infantry Regiment of World War I. Held at Curtiss Field on Long Island near New

York City and sponsored by her friend Abbott and the Chicago Defender newspaper, the show billed Coleman

as “the world’s greatest woman flier.”

On April 30, 1926 Coleman died in a plane crash while testing a new aircraft in Jacksonville, Florida. She had

recently purchased a Curtiss JN-4 (Jenny) in Dallas. Her mechanic and publicity agent, 24-year-old William D.

Wills, flew the plane from Dallas in preparation for an airshow but had to make three forced landings along

the way because the plane had been so poorly maintained. Her family and friends tried to talk her out of flying

it, but she did anyway.

On take-off, Wills was flying the plane with Coleman in the other seat. She had not put on her seat belt

because she was planning a parachute jump for the next day and wanted to look over the cockpit to examine

the fields below. About ten minutes into the flight, the plane unexpectedly went into a dive and then a spin at

3,000 feet above the ground.

Coleman was thrown from the plane at 2,000 feet and died instantly when she hit the ground. William Wills

was unable to regain control of the plane and it plummeted to the ground. Wills died upon impact and the

plane exploded and burst into flames. Although the wreckage of the plane was badly burned, it was later

discovered that a wrench used to service the engine had jammed the controls. Coleman was 34 years old.

Funeral services were held in Florida before her body was sent back to Chicago. While there was little

mention in most media, news of her death was widely carried in the African American press and 10,000

mourners attended ceremonies in Chicago, which were led by activist Ida B. Wells.

Today, many airports have roads named in Bessie’s honor, including the small airport here in her birthplace of Atlanta. Roads at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago, Oakland International

Airport in Oakland, California, Tampa International Airport in Florida, LAX in Los Angeles, and at

Germany’s Frankfurt International Airport also bear her name.

The U.S. Postal Service issued a 32-cent stamp honoring Coleman in 1995. The Bessie Coleman

Commemorative is the 18th in the U.S. Postal Service Black Heritage series. It was first unveiled during a

ceremony at the Atlanta post office – the first time a stamp had premiered in our town.

In 2001, Coleman was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. In 2006, she was inducted into

the National Aviation Hall of Fame. In 2014, Coleman was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of

Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.

.

Just in time for Black History Month 2023, the Mattel Corporation introduced the new Bessie Coleman

Barbie doll in the Barbie Inspiring Women line.

“With an unwavering determination, Bessie became the first Black woman and Native-American

woman pilot. Despite all crosswinds, she achieved her dream of flying and dedicated her legacy to encouraging

more people of color to pursue aviation,” said a Mattel Corporation spokesman.

Her pioneering role was an inspiration to early female pilots and to the African American and Native

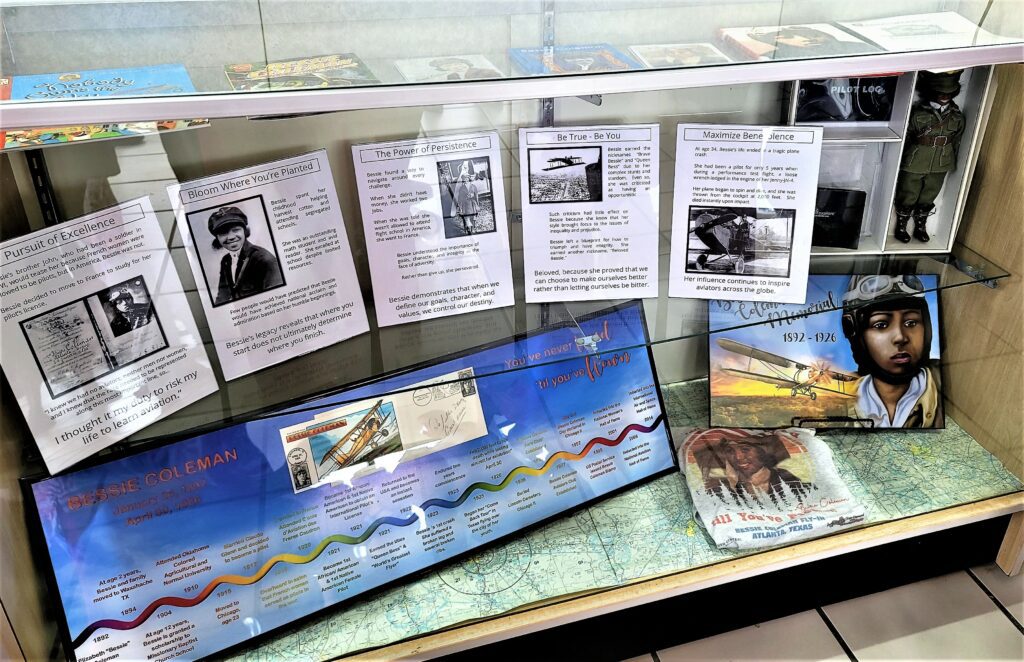

American communities. To learn more about Bessie, visit the Regional Historical Museum in Atlanta, Texas, or visit the terminal at the Hall-Miller Airport in Atlanta to see the display dedicated to her.