By Kate Stow

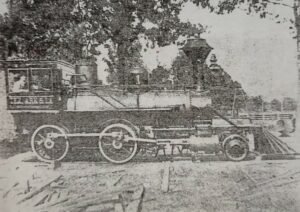

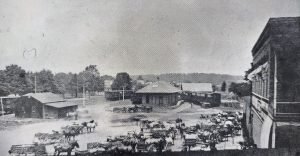

In 1897 a short-line railway was built between Atlanta and Bloomburg, connecting the Texas and Pacific Railroad in Atlanta with the Kansas City Southern line that stopped in Bloomburg, eight miles away. A small depot for the line was built where the Roux-Ga-Roux restaurant is now located, and the train made two round trips daily for twenty years.

Three engines were built by the Boyd Cleveland Iron Works and Foundry in Queen City. The trains had no whistle for the first three months and it was during this time that it received its nickname – The Dummy.

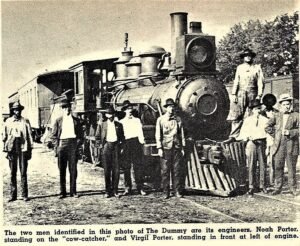

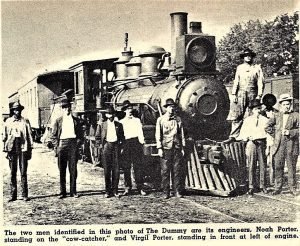

R.S Allday, who conceived the idea of the railroad, was its executive director, and Ben F. Ellington, a local cotton buyer, held the controlling interest, although nearly every merchant in the area had stock in the enterprise. Brothers Noah and Virgil Porter were the engineers and took turns in the conductor seat.

The tracks for the dummy paralleled the tracks of the Texas and Pacific Railroad out of Atlanta then wound east toward Bloomburg. The line was full of steep hills and tight curves, the steepest being “Jug Factory Hill.” It was called that because the pottery factory was located halfway up the incline.

On rainy days the train would sometimes slip on the tracks and have to back up to the depot to get a fresh start. Sometimes several tries were necessary before the little train managed to top the hill and give a proud blast. The first run left Atlanta at 8 a.m. and returned at 11:30. The afternoon run departed at 3 p.m. and returned at 5:30 p.m. The Dummy consisted of the passenger coach and usually six carloads of freight.

Since the Dummy did not have a water tank or a turntable, after each day’s second run, the crew would back the little engine down the track three blocks from the depot where a creek ran under the tracks. The crew then bolted a steam pump to a couple of cross ties on the banks, connected a pipe from the pump to the side boiler, connected a hose on the discharge side of the pump and the other end was put in the creek to fill the tender. Afterward the train traveled a few more blocks to a switch which routed it onto another section of track. After travelling the Y-shaped circuit the engine was turned around and headed toward Bloomburg for the next days’ run.

Locally, the chief crops at that time were cotton and potatoes. June was the peak month for potatoes and 150-200 carloads were often brought to the loading platform during the month. Then in the fall as many as 16,000 to 18,000 bales of cotton were carried. Hay and feed also were transported to the Texas and Pacific and Kansas City Southern connections.

A half cord of wood was required to fire up the Dummy’s engine for its morning trip. Two area farmers, Irby B. Price and his brother, cleared land in Tom Woods’ fields near Queen City and sold the wood to the railroad for 85 cents a cord. They stacked the wood alongside the tracks for the trainmen to pick up on the afternoon run back to Atlanta. The Dummy then stopped to have the wood loaded; the passengers sometimes helped in order to save time.

In 1912 a natural gas line was laid from Atlanta to Bloomburg. The railroad directors decided to experiment with the new fuel. A large tank was mounted on a flat car and coupled to the engine. Regular air hoses were used to fill the tank and it took about 30 minutes to put 100 pounds in it. This was the only vehicle of its kind to run on natural gas before or since but the noble experiment failed after only three months.

Because they were having trouble with their gas lines blowing, the gas company cut the trains line pressure to 50 pounds, half the original amount. This ration was not enough for the little train, and it consistently died two miles short of its destination.

The tank was disassembled and the flat car was made into an open air passenger car. The ride was nice and cool, but passengers had to endure the cinders and insects.

Noah Porter’s daughter, Alene Harden, was interviewed by the Journal in 1972 and she shared some vivid and pleasant memories of riding with her father and being allowed to ring the bell. She recalled that during the Louisiana State Fair, the train would run on Sundays to carry passengers to Bloomburg to catch the early train to Shreveport. It would wait for the passengers in Bloomburg and return late Sunday night.

According to the article, Harden recalled another depot, located on the thousand-acre J.J. Casey Farm, which was used for storing produce such as potatoes, peaches and watermelons. She remembers the round house, near what is now Holly Street, where repairs were constantly made on the three engines belonging to the railroad.

She said she remembered when the train was sacrificed during the first World War; one engine was sold to the Waterman Mill in Louisiana and she believed another was taken to Arkansas, and the third was used for scrap.

Noah Porter had moved his family to Atlanta in the early 1870s from Bright Star, Arkansas, and they were among the first citizens of Atlanta. They owned the first livery stable, originally located on West Street, Made in the Shade stands now, and they owned the land where the library is.

A saddened community was lined up by the tracks when The Dummy made its last run in 1918. In 1972 when excavation work was done for the building of Holly Street from town to the high school, a few of the old crossties were uncovered. Time and progress have erased all proof that The Dummy – a train that once was the most progressive of its time – had ever existed at all.